Hospital-acquired pressure injuries (HAPIs) are a serious yet preventable complication that affects more than 2.5 million patients in the U.S. each year. arise from prolonged, unrelieved pressure, particularly in critically ill adult patients who are immobile and medically compromised, leading to extended hospital stays, increased costs, and reduced quality of life (Emory University, 2021; Gupta et al., 2020). The Joint Commission (2022) classifies HAPIs as a critical patient safety issue. With the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) no longer reimbursing hospitals for pressure injuries acquired during hospitalization, many facilities have implemented prevention protocols. However, inconsistent guidelines often overlook evidence-based education and training, leading to gaps in healthcare. These injuries lead to nearly 60,000 deaths and drive up healthcare costs by approximately $26 billion annually (National Pressure Injury Advisory Panel [NPIAP], 2022).

Despite prevention protocols, HAPI rates continue to rise—especially among critically ill patients. A primary cause? Inadequate staff training and inconsistent application of evidence-based strategies (Coventry et al., 2024; Gupta et al., 2020). A new quality improvement initiative is tackling the issue by focusing on what research shows works best: ongoing education.

Reframing the Problem with a Proven Question

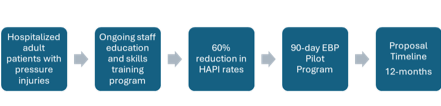

The initiative is structured around this PICOT question:

In hospitalized adult patients with pressure injuries (P), how does ongoing staff education and training on pressure injury prevention (I) compared to no education (C) affect the prevalence of HAPIs (O) over a period of one year (T)?

To answer it, a team of nursing and wound care professionals has developed a comprehensive, evidence-based

education and training program. Key components include:

Online competency modules based on national guidelines provided by the NPIAP

Monthly hands-on bedside training led by certified wound care specialists

Quarterly Skills Days to reinforce practice in an engaging, team-oriented setting

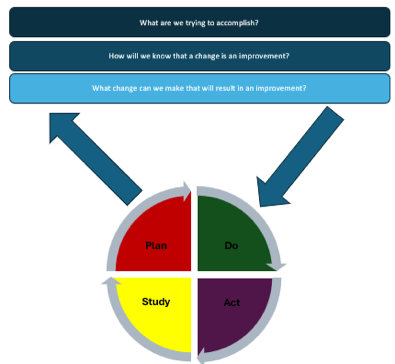

This intervention is guided by the Model for Improvement and uses the Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) cycle to continuously refine the process and improve outcomes (Melnyk & Fineout-Overholt, 2019). This project made effective use of evidence-based practice guidelines to influence therapeutic management choices and shape policy development.

Why This Approach Works

HAPIs increase patient suffering, length of stay, and are often costly. Yet, they are preventable. Treating a severe pressure injury can cost over $6,200 per patient per day—while prevention costs less than $100 per staff member daily (Padula et al., 2019).

The evidence is compelling: Singh et al. (2023) reported a 90% reduction in HAPIs after implementing a training and prevention protocol. Similarly, Kitamura et al. (2023) confirmed in a meta-analysis that educational interventions aimed at nursing staff consistently lead to improved patient outcomes.

Creating a Culture of Prevention

This initiative doesn’t rely solely on policy—it emphasizes team engagement, clinical leadership, and staff empowerment. A newly formed interdisciplinary Skin Task Force oversees training and auditing, ensuring widespread adoption and accountability.

A 90-day pilot will be initially conducted in high-risk units like the intensive care units (ICU). After the pilot, the program will expand facility-wide. The target: a 60% reduction in HAPI prevalence in one year.

Key Takeaways

HAPIs are preventable through structured, continuous staff education.

Evidence-based training programs improve skills, reduce injury rates, and lower costs.

Multidisciplinary collaboration and continuous quality improvement are essential to sustainable change.

Supporting Research

The initiative draws on numerous high-quality studies, including:

Aningalan & Gannon (2023): Achieved and sustained zero HAPI rates after implementation of a comprehensive HAPI protocol.

Romito et al. (2024); McFee et al. (2023): Reported significant HAPI reductions after implementing prevention bundles.

Kandula (2025): Highlighted the effectiveness of multifaceted, education-centered approaches in a systematic review.

Kitamura et al. (2023): Meta-analysis reinforcing that educational interventions significantly reduce HAPI incidence.

Appendices

Appendix A: PICOT Concept Map

(AHRQ, n.d.; EUAP et al., 2019; The Joint Commission, 2022)

Appendix B:

Conceptual Model: Model for Improvement (PDSA Cycle)

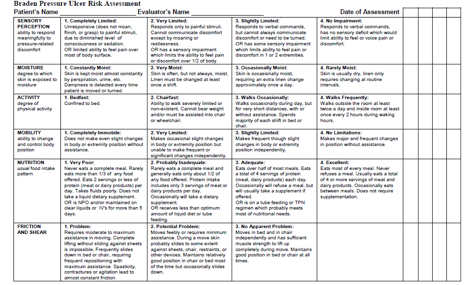

Appendix C: Braden Risk Assessment Scale (AHRQ, n.d.)

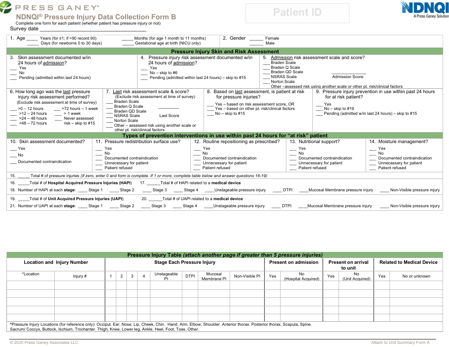

Appendix D: Press Ganey Pressure Injury Data Collection Form (Press Ganey Associates, 2020)

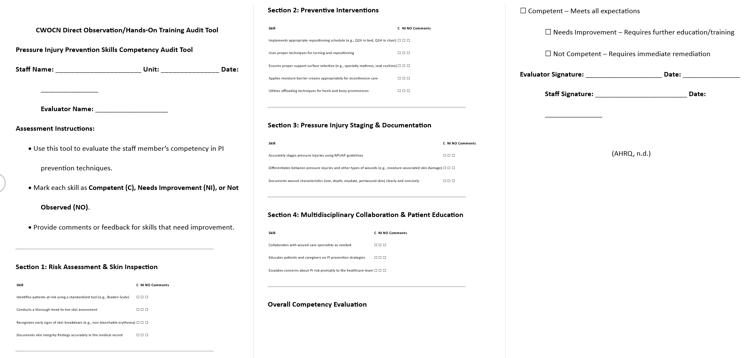

Appendix E: CWOCN Direct Observation/Hands-On Training Audit Tool

Pressure Injury Prevention Skills Competency Audit Tool

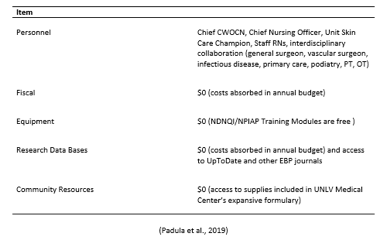

Appendix F: Resource List (Padula, 2019)

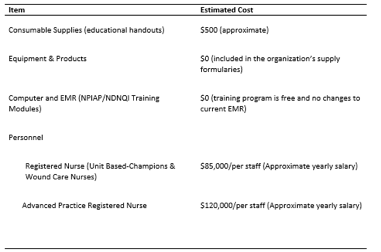

Appendix G: Budget (Padula, 2019)

Advanced Practice Providers (APPs), especially Nurse Practitioners (NPs) and Certified Wound Ostomy Continence Nurses (CWOCNs) play a pivotal role in implementing and leading these efforts. Through risk assessment, staff education, and patient advocacy, APPs help create a lasting culture of safety and excellence in care.

The full version of this article includes appendices that include evidence synthesis table, QI proposal outline, PICOT concept map, PDSA cycle and implementation timeline, audit tools, and other in-depth resources for replication, training, and evaluation. To request the complete list of references or the unedited format of the article, please contact: Mary De La Cruz at [email protected]. Please note that budget analysis and resource requirements may differ per facility and the above article may not reflect the unique needs of individual facilities. It is encouraged that each facility undergo a thorough review of financial capabilities to implement similar improvement initiatives.

References

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). (n.d.). Preventing pressure ulcers in hospitals: A toolkit for improving quality of care (HHSA 290200600012-5). https://www.ahrq.gov/sites/default/files/publications/files/putoolkit.pdf/

Aningalan, A. M., & Gannon, B. (2023). Driving hospital-acquired pressure injuries to zero: A quality improvement project. Advances in Skin and Wound Care, 36, 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1097/ASW.0000000000000056

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS). (2024). Hospital-acquired condition reduction program. https://www.cms.gov/medicare/quality/value-based-programs/hospital-acquiredconditions#:~:text=What%20is%20the%20Hospital%2DAcquired,infections%20associated%20with%20health%20care

Coventry, L., Towell-Barnard, A., Winderbaum, J., Walsh, N., Jenkins, M., & Beeckman, D. (2024). Nurse knowledge, attitudes, and barriers to pressure injuries: Across-sectional study in an Australian metropolitan teaching hospital. Journal of Tissue Viability, 33(4), 792–801. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtv.2024.10.003

Emory University. (2021). Skin and Wound Lecture Notes: Wound Core Content. European Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel, National Pressure Injury Advisory Panel, & Pan Pacific Pressure Injury Alliance. (2019). Prevention and Treatment of Pressure Ulcers/Injuries: Clinical Practice Guideline. International Guideline 2019. https://npiap.com/general/custom.asp?page=InternationalGuidelines

Gupta, P., Shiju, S., Chacko, G., Thomas, M., Abas, A., Savarimuthu, I., Omari, E., Al-Balushi, S., Jessymol, P., Mathew, S., Quinto, M., McDonald, I., & Andrews, W. (2020). A quality improvement programme to reduce hospital-acquired pressure injuries. BMJ Open Quality, 9(3), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjoq-2019-000905

The Joint Commission. (2022, March). Quick safety issue 25: Preventing pressure injuries. Quick Safety. https://www.jointcommission.org/resources/news-and-multimedia/newsletters/

Kandula, U. R. (2025). Impact of multifaceted interventions on pressure injury prevention: A systematic review. BMC Nursing, 24(11), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12912-024-02558-9

Kitamura, J. C., Nicolosi, J. T., Paggiaro, A. O., & de Carvalho, V. F. (2023). Educational interventions on preventing pressure injuries targeted at nurses: Systematic review and meta-analysis. British Journal of Nursing, 32(20), S40–S50. https://doi.org/10.12968/bjon.2023.32.Sup20.S40

Melnyk, B. M., & Fineout-Overholt, E. (Eds.). (2019). Evidence-based practice in nursing & healthcare: A guide to best practice (Fourth ed.). Wolters Kluwer. National Pressure Injury Advisory Panel. (2022). 2022 PI incidence statistics. https://npiap.com/page/2022WWPIPD

Padula, W. V., Pronovost, P. J., Makic, M. B. F., Wald, H. L., Moran., D., Mishra, M. K., & Meltzer, D. O. (2019). Value of hospital resources for effective pressure injury prevention: A cost-effectiveness analysis. BMJ Quality & Safety, 28(2), 132–141. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjqs-2017-007505

Press Ganey Associates, LLC. (2020). NDNQI pressure injury data collection form [Form]. https://content.sitelms.org/course-brochure/37470.pdf

Romito, K., Talbot, L. A., Metter, E. J., Smith, A. L., Hartmann, J. M., & Bradley, D. F., Jr. (2024). Perioperative pressure injury prevention program in a military medical treatment facility: A quality improvement project. Military Medicine, 189(S1), 51–56. https://doi.org/10.1093/milmed/usad321

Singh, C., Shoqirat, N., Thorpe, L., & Villanueva, S. (2023). Sustainable pressure injury prevention. BMJ Open Quality, 12, Article e002248. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjoq-2022-002248